Rarely has a contemporary geopolitical discourse so clearly trampled on reality as Putin’s defence of the war against Ukraine. Yes, we used to put the word ‘reality’ in quotation marks because we learned that ‘facts’ are a language thing and that reality consequently is a creation. Does our habituation of a world created by ‘influencers’ spell the end of the world order as a source of international justice, whatever the actions to punish Putin and Russia may yield? Such questions of rightness and reality have dominated my own intellectual life for a long time.

If any interests were deeply buried in my DNA they are a gift for technology (particularly electronics) and love of nature. None of it would determine my professional career although it certainly inspired my teenage dreams of an advanced study in electronics and somewhat later in biology (which I studied for a year in 1963-4). Actually my long term professional interest would be better defined as ‘human (mis)perception, particularly as manifested in politics. Some experiences in my younger years may, in hindsight, have been decisive for this outcome. As a passionate observer of plant- and bird-life in a large estate just across our street, I was deeply grieved when they started to transform my paradise into a complex of buildings, worse: a university campus. It made me rethink the idea of progress and I discovered for myself at the age of 14 what Max Weber had stated long before in terms like “absolute progress does not exist”. Progress can only be established value-free in a search for more effective means to reach a well-defined goal. But goals themselves are never value-free. Preventing a worldwide ecological disaster may come close to such a thing but this universally acclaimed goal is overwhelmed by self-serving policy proposals.

How language is used to seduce people in mixing fact and fiction became a favourite perspective since the 1970s (discourse studies and poststructuralism). I was particularly inspired by the work of a sociologist like Peter Manning who pioneered a more organizational approach in his study of the police by showing how the productivity of such organizations may be biased by their own decisions to do what they can most easily achieve. It revealed a logic in constructing our reality and inspired my PhD thesis about the construction of the police image of the local environment of Amsterdam (1987). This work, however, never seduced me to adopt the extreme post-structural conclusion that ‘facts do not exist’ (Baudrillard, etc.). Actually I found that the police themselves were much aware of the tension between their data and (false) representations of urban space in the public. In any way, their data did not help them to ease their job.

The whole desire to construct a ‘logical world’ became acute at a the national level when the frozen Cold War borders collapsed in Europe at the end of the 1980s. As a political geographer I immediately sensed that it would not merely bring ‘freedom’ but also a new need for demarcation that could spell war. During a study trip in 1990 with master students to some of the former communist countries (among which Yugoslavia)* I was amazed how little my students could imagine the new (political) identity problems that tried these people. It was this naiveté in the West that urged me to write ‘National Identity and Geopolitical Visons’ (1996).

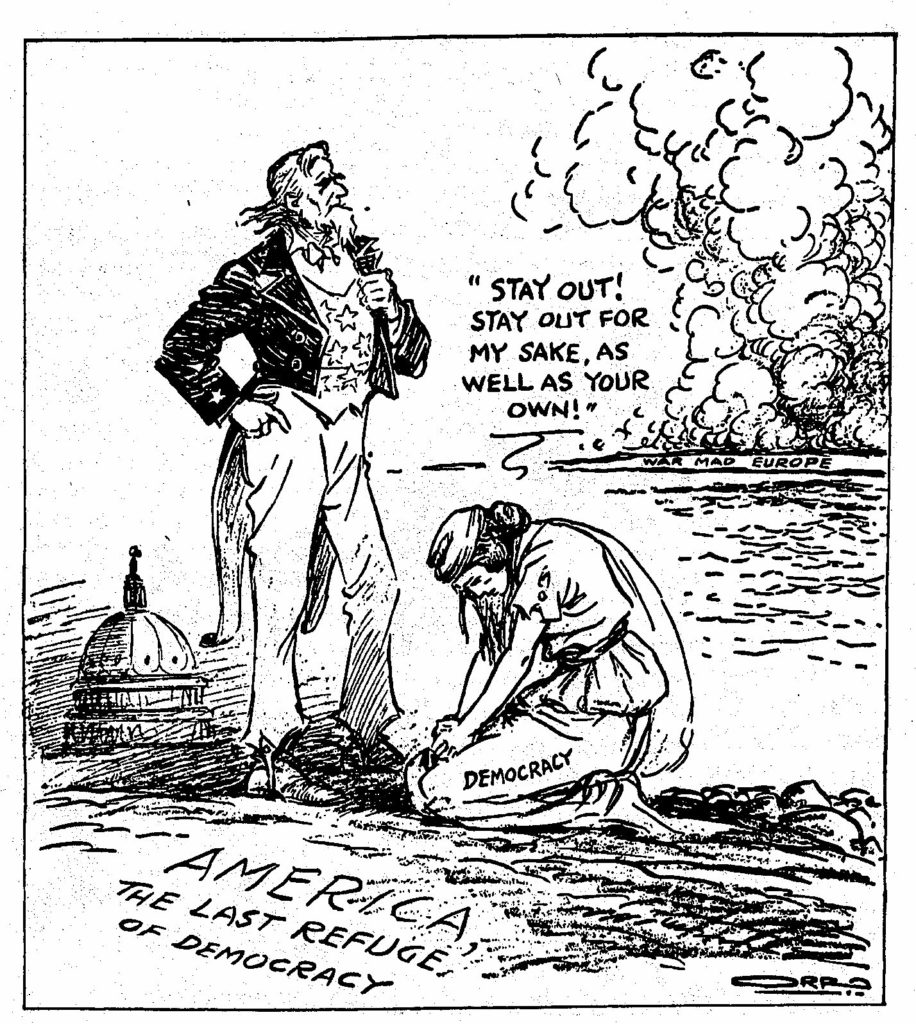

The problem however re-surfaced after the ethnic wars in former Yugoslavia had been checked with the help of international intervention. Recent tensions in Bosnia-Hercegovina already smashed the vain hope that an exposure to the forces of globalization might have softened the need for territorial demarcation. Similarly the current Russian occupation of Ukraine is another example of a need to reinforce one’s boundaries. Much of this is shocking for those who believe in the benign force of globalization, a vision that thrives particularly in the European Union. My book ‘Territorial Shock’ (2018) raised the question how states, prompted by their decreasing autonomous power, adapt to the process of globalization. In order to establish a clear response to globalization in a nation’s foreign politics one should particularly look at adaptations that follow on total collapse, a ‘reset’ like the procedure applied to failing electronics. In other cases foreign policies may appear as a more vague continuation of tradition, albeit with small adaptations. The condition of a reset occurs in states that have been conquered by a foreign power, that have been dissolved or that have been ravaged by civil war. Looking at France (rising after World War II), Russia (after the dissolution of its empire) and Somalia (civil war) I discerned three types of reaction: multinational governance (EU), imperialism and ‘glocalism’. Russian imperialism has received a new impetus since 1990.

Only by liberating media and political speech from all attempts of mind control can we hope to move Russia into the sphere of multinational governance. Losing a war did the job in Europe and a failure of the Ukrainian expedition may do the same in Russia. The latter, however, may ask a a prolonged action of all democratic nations and the contribution of groups such as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

*I organized the trip together with my colleague Petr Dostal who in 1998 became a professor at Charles University in Prague and sadly died in 2021.